An ancient meditation tool………

An ancient meditation tool………

……..for the new millennium

The labyrinth is a pattern with a purpose – it shows us that no time or effort is ever wasted: if we stay the course, every step however circuitous, takes us closer to our goal. Its many turns reflect the journey of life which involves change and transition.

Many people make the mistake of thinking a labyrinth and a maze are the same. A maze has dead ends and may trick turns. A labyrinth is a single path that takes you to the centre and is not designed to have you lose your way, but help you find it. The fact that there is only one path allows you to release your worry about where you are going. But it is quite a structured path, so it demands that you focus on where you are at the moment, so you let go of the past.

Many people make the mistake of thinking a labyrinth and a maze are the same. A maze has dead ends and may trick turns. A labyrinth is a single path that takes you to the centre and is not designed to have you lose your way, but help you find it. The fact that there is only one path allows you to release your worry about where you are going. But it is quite a structured path, so it demands that you focus on where you are at the moment, so you let go of the past.

Thinking is not required to walk a labyrinth, at the same time one must remain alert to stay on the path. As reaching the centre is assured, walking the labyrinth is more about the journey than the destination, about being rather than doing.

Walking the labyrinth clears the mind, calms people in the throes of life transitions, it helps see life in the context of a path, a pilgrimage. One can realise we are not human beings on a spiritual path but spiritual beings on a human path.

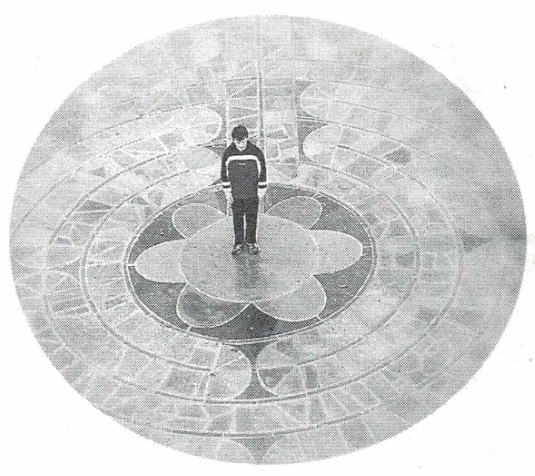

Shrule millennium labyrinth

Labyrinths are found in many sizes and shapes. Some are created in sand, flour, painted on canvas, cut into turf, formed by mounds of earth or many other natural materials, some are permanent structures. The labyrinth of Shrule is permanent, built from stone.

The design is medieval, it is the classical 11 circuit labyrinth. Over a period of five months the project was completed, made possible by the many people of the area using their individual talents. Each stone of the labyrinth was cut to fit the distinctive design. The outer circle has a diameter of 13m. (42ft.). The path is of Lacken sandstone, quarried beside the sea in North Mayo. The other stone used in the labyrinth is limestone, the stone native to this area.

The design is medieval, it is the classical 11 circuit labyrinth. Over a period of five months the project was completed, made possible by the many people of the area using their individual talents. Each stone of the labyrinth was cut to fit the distinctive design. The outer circle has a diameter of 13m. (42ft.). The path is of Lacken sandstone, quarried beside the sea in North Mayo. The other stone used in the labyrinth is limestone, the stone native to this area.

The sandstone path is 40cm. (16ins) wide, the limestone barrier is 5cm. (2ins). You walk the sandstone path and you do not step across the limestone sections. The walking path is 275 metres (300yds), so to walk the labyrinth from the west side, marked by a black Kilkenny limestone from the old Dalgan House.

The centre is a single stone, a sandstone of diameter 1.5m (5ft). It is surrounded by six petals traditionally said to symbolise mineral, vegetable, animal, human, angelic and divine, six stages of planetary evolution. The entire central design is a circle of diameter 9ft.

After the twists and turns of the walk the centre should be a place of space and peace where one pauses for some moments before one meanders back and forth again on the return journey.

After the twists and turns of the walk the centre should be a place of space and peace where one pauses for some moments before one meanders back and forth again on the return journey.

Lunations are the outer ring of triangles that completes the outside circle of the labyrinth. There is a total of 113 triangles one absent in the design at the entrance – these mark 28 points per quadrant on the outer ring. Some believe the labyrinth served as a calendar and this offered a method of keeping track of the lunar months of 28 days.

Walking a Sacred Path.

The tradition of pilgrimage, of going or walking, is as old as religion itself – whether it is the Ka’aba in Mecca, the Ganges in India or the Easter festivals in Jerusalem.

In the Middle Ages, most people did not read and were much more oriented to the senses than we are today. People walked to holy places, many in search of physical or spiritual healing. In the twelfth century, when the Crusades swept across Europe and Jerusalem became the centre of religious struggle, travel became dangerous and expensive. Some cathedrals were appointed pilgrimage cathedrals, to become the “Jerusalem for pilgrims”. The walking of the labyrinth in these cathedrals marked the ritual ending of the journey across the countryside. In the tradition of pilgrimage the path of the labyrinth is called the “Road to Jerusalem”.

Many to-day walk labyrinths still searching, how one walks and what one receives differs with each person. Some walk to clear the mind, some with a question, some to reflect, meditate or pray, others walk to discover ones own sacred inner space. Some walk it just as a pleasant walk, some just follow a person ahead. Many, certainly the first time, walk it to assure themselves that they will reach the centre. The labyrinth slows us down, offers a chance to take “time out”. Walking a labyrinth is a gift we give to ourselves, it calls on us to “waste time” or find time for ourselves, for our own journeys and to discover their pattern. In the labyrinth our life patterns become clear, some are impatient others are hesitant, some seek directions others offer advice, some lead the way others follows, some try visually to figure out where the path goes, others are content to await the turns. Each time is different and like any pilgrim path, the reason why and one’s experience is personal.

How to walk the labyrinth.

· You enter from the west, from the black stone – the only gap in the circle of brown triangular lunations

· You do not step across limestone, it always marks a turn.

· Go at a pace that is natural to you.

· Commit yourself to the whole walk, in and out.

· Respect the journey of others.

· Walk in silence. Walk mindfully and respect other’s silence too.

· Pause at the centre. Many move form petal to petal, a reminder you are part of the whole, before retracing their steps back out.

· Do not burden yourself with great expectations

“Why on earth am I doing this anyway, when I’ve clearly got so much else to do?”. At the centre I felt a sense of accomplishment, by the time I had walked out of the Labyrinth the other trivia from my mind had long gone. I have to confess, serenity had replaces scepticism – but I think it is possible I was spiritually enriched. Well! I’m ready to tackle matters more important.’

(Times Feb. ’99)

Theseus and the Minotaur

Labyrinths have been around for over 4000 years and are found in just about every major religious tradition in the world. They have been an integral part of many cultures such as Native America, Greek, Celtic and Mayan. Like Stonehenge and the pyramids, they are magical geometric forms that define sacred space.

The greatest labyrinth in the world no longer exists. Built by the Egyptian King Amenemher about 2000 B.C. beside his pyramid at Fayum, it was more than 1000 metres in circumference. The oldest known pattern in Ireland comes from a stone inscription in Hollywood, Co. Wicklow. The best-known labyrinth of antiquity was that of the Minotaur at Knossos in Crete. This creature, half man and half bull lived in the labyrinth. Every nine years King Minos of Crete demanded seven youths and seven maidens be sent from Athens, they were sent into the labyrinth and were devoured by the Minotaur. Theseus, son of King Aegeus of Athens, was so moved by the sorrow of the parents who had to send their children to Crete that he volunteered to go and be one of the victims if he was unable to kill the Minotaur. When Theseus arrived at the palace of Knossos, Ariadne – the daughter of King Minos instantly fell in love with him. She promised to help him kill the Minotaur if he would marry her and take her to Athens. She then helped him to enter the labyrinth and gave him a ball of red thread and a sword. The plan was successful and he was able to kill the Minotaur and return safely to the entrance and Ariadne. The story does not end happily, on the return journey to Athens the vessel stopped at the port of Naxos. Ariadne strayed apart and fell asleep, Theseus sailed on leaving her alone on the island. It is rather Ironic that the labyrinth of the Minotaur could scarcely have been a labyrinth at all, if there was only a single route in and out there would have been no need of a ball of thread?

The greatest labyrinth in the world no longer exists. Built by the Egyptian King Amenemher about 2000 B.C. beside his pyramid at Fayum, it was more than 1000 metres in circumference. The oldest known pattern in Ireland comes from a stone inscription in Hollywood, Co. Wicklow. The best-known labyrinth of antiquity was that of the Minotaur at Knossos in Crete. This creature, half man and half bull lived in the labyrinth. Every nine years King Minos of Crete demanded seven youths and seven maidens be sent from Athens, they were sent into the labyrinth and were devoured by the Minotaur. Theseus, son of King Aegeus of Athens, was so moved by the sorrow of the parents who had to send their children to Crete that he volunteered to go and be one of the victims if he was unable to kill the Minotaur. When Theseus arrived at the palace of Knossos, Ariadne – the daughter of King Minos instantly fell in love with him. She promised to help him kill the Minotaur if he would marry her and take her to Athens. She then helped him to enter the labyrinth and gave him a ball of red thread and a sword. The plan was successful and he was able to kill the Minotaur and return safely to the entrance and Ariadne. The story does not end happily, on the return journey to Athens the vessel stopped at the port of Naxos. Ariadne strayed apart and fell asleep, Theseus sailed on leaving her alone on the island. It is rather Ironic that the labyrinth of the Minotaur could scarcely have been a labyrinth at all, if there was only a single route in and out there would have been no need of a ball of thread?

Perhaps this is why in common speech the words labyrinth and maze are interchangeable.